http://www.startribune.com/gallery-armi ... 4802482/#1Anderson: During Armistice Day Blizzard of 1940, it 'seemed too nice to hunt'

The snow came first, beginning in early afternoon, with big flakes covering the ground. The wind — up to 80 miles an hour — and precipitous temperature drops of as much as 50 degrees followed.

November 11, 2015 — 8:25am

"Rescue workers carried out the body of one of three St. Paul hunters who had taken a boat onto North Lake near Red Wing, Minn."

http://stmedia.startribune.com/images/2 ... zz.gal.jpgGallery: 1/13

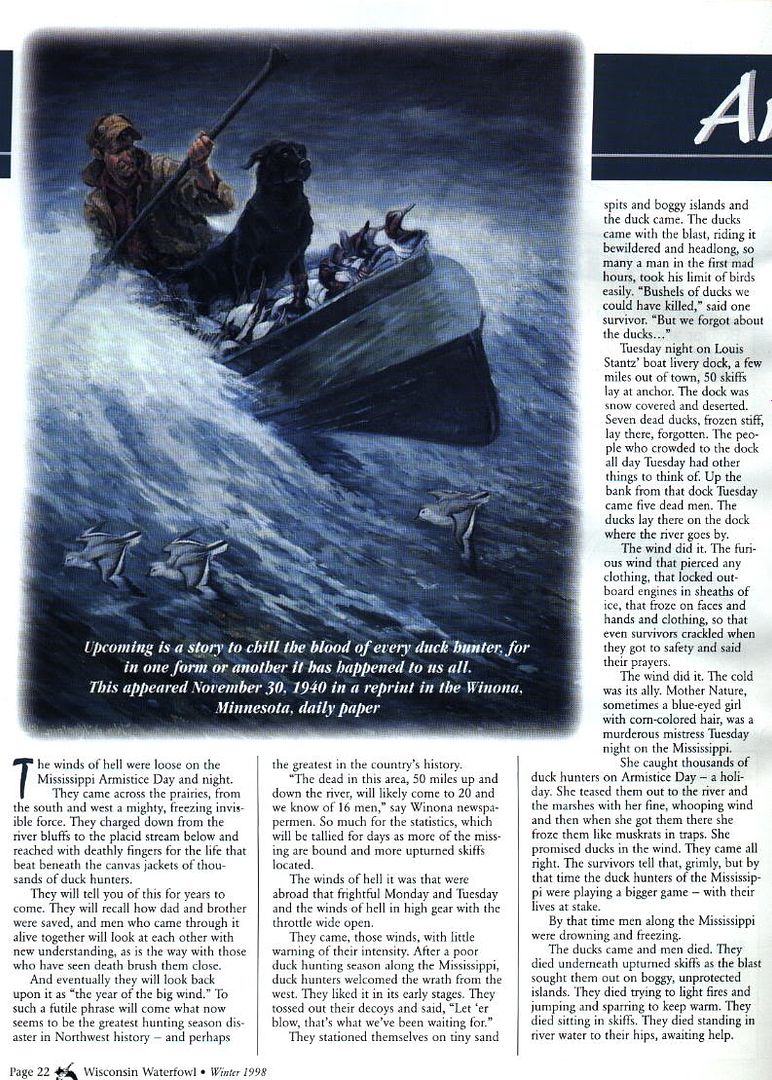

There was large loss of life in part because the storm came early in the season and occurred on a holiday immediately following a weekend. Many hunters were caught away from adequate shelter throughout the state. Shown here are two of many duck hunters and others who died.

http://stmedia.startribune.com/images/2 ... zz.gal.jpgDENNIS ANDERSON Dennis Anderson @stribdennis

School was held that day in La Crosse, Wis., but only in the morning. No classes were taught. Instead, students attended a program highlighting the sacrifices veterans had made for their country. Then the kids were dismissed. It was, after all, a national holiday, Armistice Day.

This was in 1940, and matters were unsettled, worldwide. Officially, the U.S. was on the sidelines of gathering war clouds in Europe. Americans were long tired of conflict and of the remnants of the Great Depression. Yet the country could feel itself being dragged into war, dark and foreboding, and its prospects cast a pall over everything.

In La Crosse, Dick Bice, 16, and his pal La Vern Rieber, 18, drove from school to their homes and then to Brice Prairie, Wis., deciding to look for ducks on Lake Onalaska on the Mississippi River. At 4 miles wide, the “lake” is the widest spot in the big river, and though the weather was mild, with scant winds, the boys set out with anticipation, wooden decoys piled in their narrow skiff.

Meanwhile, Bice’s brother Jim, 17, also a duck hunter, stayed home. “The weather seemed too nice to hunt,” he recalled Monday.

Now 92 and still living in La Crosse, Jim Bice remembers Nov. 11, 1940, like it was yesterday.

“It didn’t start out like a duck hunting day,” he said.

In fact, that entire fall had been extraordinarily warm, with October and early November temperatures well above average.

Consequently, Mississippi River duck hunters hadn’t had much good shooting.

The big migration, they believed, was yet to come.

• • •

The boat Dick Bice and La Vern Rieber paddled onto the Mississippi was a homemade job, as most river hunting skiffs were at the time. With a flat plywood bottom and low freeboard, it could hold two hunters, maybe three. On this day, Rieber’s retrieving dog also was along.

Duck hunting was good sport back then. Minnesota had about 120,000 duck hunters in 1940 (out of a population of 2.79 million), compared with 80,000 today (out of 5.5 million residents). The duck harvest was much larger, too: 1.6 million in 1940, compared with 650,000 today.

Because Armistice Day — now Veterans Day — fell on a Monday in 1940, the Mississippi saw a high turnout of waterfowlers that day. With a rumored weather change pending, hunters believed the long-awaited migration might begin in earnest.

So it was that near Red Wing and Wabasha, and farther south to the Weaver Bottoms and to Winona and Lake Onalaska farther south still, hunters by the score paddled and in some cases motored into the river’s currents toward its backwaters.

Justifiably, they had high hopes. After a string of seasons only 45 days long, waterfowlers in 1940 were allowed 60 days in the field.

Shooting hours also were liberalized. Previously allowed only from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., shooting in 1940 could begin instead at sunrise. And while the daily duck limit remained unchanged at 10, a new rule in 1940 allowed hunters to possess double their daily limits for up to 20 days after the season’s close, rather than 10 days, as was previously the case.

• • •

The snow came first, beginning in early afternoon, with big flakes covering the ground. The wind — up to 80 miles an hour — and precipitous temperature drops of as much as 50 degrees followed thereafter.

Weather forecasting and communication 75 years ago weren’t what they are today, and by the time the ferocity and breadth — up to 1,000 miles wide — of the storm were realized, the fates of about 150 people were sealed.

Duck hunters on the Mississippi were particularly at risk. Most had dressed only for the fairest weather, with light jackets and pants.

Most also — at first — were delighted that the weather brought with it huge influxes of ducks. Mallards that typically circled and circled before landing instead dropped fearlessly into decoys. Divers — canvasbacks, bluebills, redheads — also materialized in droves from the maelstrom.

At first, Bice and Rieber relished the good shooting. But matters turned worse when Rieber, in the skiff, chased a downed duck and couldn’t paddle back to Bice. Instead he took refuge on a small, windswept island.

Seeing Rieber stranded, but unable to rescue him, a group of passing hunters gave him a tarp. Huddling beneath it, and beneath the skiff, alternately standing and sitting, he stayed awake all night.

Bice, meanwhile, continually ran in circles, with brief intermissions. He also huddled with Rieber’s dog.

• • •

Jim Bice on what happened after Dick and La Vern didn’t return home the night of Nov. 11:

“My dad and I, and La Vern’s dad, drove to the landing where Dick and La Vern launched their boat. We found their car. But there was no sign of them.

“All night we stayed right there, in our cars, running the engines to keep the heaters on.

“On an island in the river, we could see a campfire, and we could see men walking in front of the fire. That was Dick and La Vern, we figured.

“The next morning, the lake had frozen over, and we saw the two fellas get into their boat, and the wind blew the boat to our side. As they approached, we expected to see our boys. Instead, they were two guys we didn’t know.

“They told us they had heard shooting upriver of where they were.

“We waited hours until the ice got thicker, and when it did, my dad and the other men walked upriver until they found Dick and La Vern.

“La Vern had the skiff, which he used for shelter, and Dick had the dog. We got them to shore and to a hospital. They both checked out all right.”

Richard “Dick” Bice died in 2003.

La Vern Rieber died in 2011.

Said Jim Bice: “At 92, I’m the only one left. I don’t think too many of us who were on the river that day, Armistice Day, are still around.”

Four searchers pulled away from a rescue launch in a smaller boat to comb Mississippi River bottomlands on Nov. 13, 1940 -- dangerous and icy work.

http://stmedia.startribune.com/images/2 ... zz.gal.jpg-----

Armistice Day Blizzard: No truces from this stormSt. Peter’s snow-covered streets were void of traffic following the Armistice Day blizzard. Wednesday is the anniversary of the 1940 storm.

http://www.mankatofreepress.com/news/lo ... ge&photo=0Posted: Monday, November 9, 2015 12:30 am

By Edie Schmierbach Free Press Staff Writer

Seventy five years ago Wednesday, Mankato residents were planning a giant parade on what started out as a balmy day. Then the temperature rapidly dropped and strong winds began to blow — a mix that formed a killer snowstorm throughout the Midwest.

The town’s focus on Nov. 11, 1940, moved from celebration to winter survival.

“You literally had a 40-degree temperature drop in six to eight hours, and that’s almost unheard of,” meteorologist Paul Douglas said. “People headed out in light jackets because the temperatures were in the 50s and 60s in the morning, and then a few hours later, it was in the 20s or 30s with gale-force winds and blinding snow.”

A total of 154 deaths was blamed on the storm, which cut a 1,000-mile-wide path through the Midwest. Sixty-six sailors died in Lake Michigan after three freighters and two smaller boats sank. Two people died when two trains collided in the blinding snow in Watkins.

Forty-nine people in Minnesota died in the storm. Half the Minnesotans who died were duck hunters.

Stanley F. Bachman, 86, was a teenager back then. “I was hunting with my dad near Cleveland.”

Bachman and his father were separated in the storm for about three hours. After they were reunited, they joined several other hunters who had found shelter at Ward and Francis Kluntz’s farm near Lake Jefferson.

“It was one of those times you never forget,” said Bachman of Bloomington.

“There were about 10 other hunters there,” he said. “We helped the farmer round up his chickens in the afternoon — that was cold work. In the evening, we helped milk cows.”

One of the storm refugees was a cook at St. Peter state hospital. “He took over the kitchen. We made hunter’s stew using rabbits, squirrels and ducks,” Bachman said.

Bachman’s never spent much time worrying about the weather. “It doesn’t bother me. It couldn’t be as bad as back then.

“My plans today are not related to the storm,” the Coast Guard veteran said in a 2010 interview. Bachman's schedule included singing patriotic songs during two choral performances.

His story is one of several featured in the book “All Hell Broke Loose: Experiences of Young People During the Armistice Day 1940 Blizzard.” William Hull collected more than 500 blizzard tales — 167 were published by Stanton Publication Services in 1985.

A teacher and her students were stranded in their one-room school near Marysburg; the Double Dip cafe in Mankato provided shelter to stranded travelers; and trains, buses and countless vehicles had to be released from drifts several feet high.

Records show that 27 inches of snow fell at Collegeville in central Minnesota. Drifts closed many highways, and many motorists left their stranded autos and froze to death before they could reach safety. About 250 St. Paul streetcars were marooned on their tracks overnight.

Patricia Rynda wrote about being a child at the time of the blizzard. It’s not the snow, but flames that first come to her mind. Her family lived a few blocks from the Westerman Lumber Co. in Montgomery, which burned to the ground Nov. 12, 1940. She remembers watching firemen struggling against the bitter cold of the storm and the fire’s heat.

Rynda remains a Minnesota resident but said she’s never learned to love winter. “I like to go south to Texas,” she said.

Douglas said the storm led to major changes in weather forecasting in the Midwest. At the time of the blizzard, the National Weather Bureau in Chicago prepared the weather forecast. After the storm, it was decided “on the spot, that, yes, the Twin Cities deserves its own local office,” he said.

Douglas, who is the CEO of Weather Nation, a company that outsources video segments to news clients, said the historic storm was remarkably intense and sudden.

“Meteorologists call it a ‘bomb,’ which means the air pressure fell at least 24 millibars in 24 hours,” he said. “Those winds can reach 40, 50, 60 miles an hour. It’s close to hurricane-force. Thankfully, they’re rare. Something like that whips up maybe once every 20 to 30 years.”

This story, first published in 2010 on the 70th anniversary of the blizzard, contains information from The Associated Press.-----

75 years later, deadly blizzard still rememberedPosted: Tuesday, November 10, 2015 6:15 pm | Updated: 7:42 pm, Tue Nov 10, 2015.

By WILLIAM MORRIS

wmorris@owatonna.comOn the rural Ellendale farm where Gail Smith grew up, the barn was only 150 feet away from the house, an easy trip he made several times a day. But when he finished his afternoon chores on Nov. 11, 1940, and set out for home, he found the going a little harder than usual.

“As soon as I came out the north barn door, the wind took my breath away,” he wrote, and it’s not a figure of speech. “The wind blew across my lips so fast it created suction in my mouth so I couldn’t breathe. I had to turn my head away from the wind.”

Assailed not just by gale-force winds but by driving snow and sleet and gathering darkness, 13-year-old Gail set out for home, but was focused so heavily on keeping his breath that he soon found himself off the path.

“Suddenly I realized I should be at the house by now,” he wrote. “I looked around and couldn’t see a thing. It was very dark, [and] snow was coming down like crazy and was being whipped by the wind to form a complete white out condition. I couldn’t even see the lights in the house.”

Gail was fortunate. After a few terrifying seconds, he stumbled across the farm outhouse, where he was able to shelter and catch his breath before making it back to the house and safety. But across Minnesota and the Midwest, almost 150 others weren’t so lucky.

University of Minnesota professor and climatologist Mark Seeley calls that storm, the Armistice Day Blizzard of 1940, a “bookmark” event, one that left an immeasurable impact on everyone who survived it. The storm dropped 16.8 inches of snow on the Twin Cities, a record that stood for more than 40 years, and as much as 27 inches in other areas. Temperatures dropped by as much as 50 degrees over the course of a day, and winds as high as 60 mph flattened utility and phone lines.

Even worse, from the perspective of residents, was the lack of warning. As late as the morning of the 11th, the forecast out of Chicago was still calling just for a moderate cold wave.

“They did a horrible job,” Seeley said. “I don’t know all the reasons behind it but they completely missed the forecast, and over the period of about 10 in the morning … until midnight that night … the blizzard peaked in Minnesota, depositing anywhere from a foot to two feet of snow.”

For many Minnesotans, the combination was lethal. Forty-nine deaths around the state were blamed on the storm, with a particularly heavy toll among duck hunters who were trapped along the Mississippi River with no shelter and inadequate clothing. Three Steele County residents were among the missing, according to the Nov. 12 issue of The Daily People’s Press: rural schoolteachers Ve Loris Heger and Francis Robertson, and taxi driver Russell Anderson, who was dispatched at 3:30 p.m. on the 11th to bring them to safety.

The storm, which also killed 66 sailors on Lake Michigan and dozens more in other states for a total of 145, was part of the same weather system that caused the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge four days earlier in Washington state.

“[There was] just huge disruption.” Seeley said. “… Many thousands and thousands of people were stranded where they didn’t want to be, at work or at school or in trains or in bus terminals … it was just total chaos.”

In a collection of stories about rural Steele County schools published in 1979 by the Steele County Historical Society, several teachers wrote about their memories of that particular storm. Laurietta McNearney of Blooming Prairie remembered watching with her students as rain turned to snow and how she began preparing for her and 11 students all to stay overnight in the schoolhouse. Only when two drivers managed to reach the school in their cars did they dare risk leaving their shelter to try to make it home.

“We crawled along a few feet at a time, stopping many times until the wind died down enough to allow us to see a few weeds, our only means of knowing we were still on the road,” she wrote. “After crawling along at this slow pace, we deposited our load of children on their driveways and finally made it to the highway. Visibility was better there, but we found all the telephone poles and wires were down on half of the road, making it necessary to drive into a driveway until an oncoming car had passed. … Ordinarily, the trip would have taken 15 minutes, but on this day an hour was spent. We were most grateful to have made it safely home.”

Magdalen Seykora of Owatonna remembered that the fall of 1940 was unusually warm and beautiful, but on Armistice Day, all of that changed, as she remained stranded in her rural school after all the children were picked up.

“Now I was alone in this cold and dark school room with only the howling winds and broken branches, wires and sharp sleet hitting the sides of the building for company,” she wrote. “Every so often I would open the door just enough to see if anyone was coming for me. Drifts were building up and the sky was very dark.”

Seykora’s husband and brother-in-law finally arrived at 2:30 p.m. and were able to escort her out, taking her plants, perishable food and goldfish with them. But the car was blown off the road, quite literally, by the fierce storm, she wrote, and they were forced to seek shelter at a nearby home.

“I shall never forget that night in the Kaplan home,” she wrote. “We were all huddled around the kitchen stove, eating popcorn and listening to the battery radio which gave a continuous relay of messages from schools to parents that their children were safe either in the school or someone’s home ... In my 33 years of teaching, I had many heart-warming, earth-shaking, humorous and sad experiences, but the Armistice Day storm of 1940 was the one I and many of my former pupils never shall forget.”

Seeley said the Armistice Day Blizzard, along with a blizzard in March of 1941 that killed 32 and again drew no warning from the National Weather Service, prompted major changes in the way weather was predicted, including staffing weather offices 24 hours a day and launching the predecessor to the modern National Weather Service bureau in Chanhassen.

“As a result of that, later in 1941, the weather service authorized a forecast place in the Twin Cities, so Minnesota could forecast for ourselves and not just abide by the Chicago forecast,” he said.

As for Smith, who wrote up his recollections of the blizzard about the year 2000 in a booklet aptly titled, “The Day ‘All Hell Broke Loose,’” he went on to graduate from Mankato State University and work for the Navy and NASA, where he helped design early satellites and components for the Space Shuttle. Now 88 and living in Maryland, he said the near-death experience has stuck with him even 75 years later.

“It was just something that we suffered through,” he said. “I just remember this because it was so dangerous to our family and our livestock.”

Seeley said for Minnesotans of Smith’s generation, that’s only to be expected.

“There’s others that are landmark events, but the Armistice Day Blizzard in 1940 is certainly I would say one of the five worst in Minnesota history,” he said. “[It was] probably the most memorable weather event of their lives for the people who lived through that Armistice Day Blizzard.”

William Morris is a reporter for the Owatonna People’s Press.

------

From the archives: Two survivors remember Armistice Day Blizzard that killed 49By Mary Divine

mdivine@pioneerpress.comPosted: 11/11/2010 12:01:00 AM CST | Updated: 81 min. ago

Editor's note: This story was reported and written in 2010.

Norman Roloff and his best friend, Sonny Ehlers, used to get together every Armistice Day and toast their good fortune. They weren't, after all, dead.

On the afternoon of Nov. 11, 1940, the men were 19-year-olds, hunting ducks in the backwaters of the Mississippi River near Winona, Minn., when the winds began to change.

"It was so warm, I took my hunting jacket off," Roloff said. "I didn't need it. I didn't need gloves. The high was probably in the 50s or 60s."

By early afternoon, Roloff said, the skies had turned cloudy and misty.

"Then it began to rain, and the wind picked up, and we just had fabulous shooting," he said.

"We're lucky we all survived. It blew in so fast," said 82-year-old Audrey Lemm, remembering the suddenness of the Armistice Day Blizzard 70 years ago, at her home in White Bear Lake on Wednesday November 3, 2010. (Pioneer Press: Richard Marshall)

The ducks -- thousands of them -- were on the move, Roloff said.

"The ducks just kept coming," he said. "It was fabulous. Everybody around there ... you could hear the shooting everywhere."

The ducks might have had an inkling of what was in store, but the hunters didn't have a clue, Roloff said.

The rain turned to sleet. The sleet turned to snow. And kept coming. The result came to be known as the Armistice Day Blizzard of 1940.

Forty-nine people in Minnesota died in the storm. Seventy years later, for the people who survived and for the people who study it, the unforgettable event changed lives -- in ways small and large.

Audrey Lemm, 82, of White Bear Lake survived the storm. The lessons learned stuck with her. Before her daughters left the house in the winter, they were always told: "Bring your mittens. Bring your hats. Bring your coats.

"They would say, 'Oh, yeah, oh yeah,' but I always felt it was better to be safe than sorry," she said. "You don't want to get caught and not have gloves or mittens or anything like that."

Meterologist Paul Douglas said the storm led to major changes in weather forecasting in the Midwest. At the time of the blizzard, the National Weather Bureau in Chicago prepared the weather forecast.

After the storm, it was decided "on the spot, that, yes, the Twin Cities deserves its own local office," he said. "There's no substitute for living in the place that you're trying to forecast for."

Of the survivors, Roloff and Ehlers were among the most at risk. Half the Minnesotans who died were duck hunters.

Roloff, 89, and Ehlers, who died last year, met each year on Nov. 11 until the 1980s to "raise the glass" to celebrate their survival, Roloff said last week during an interview at his condominium in Bloomington. After that, they would call each other on the anniversary and reminisce.

Now, Roloff is left to remember on his own.

"There're not that many of us left," Roloff said. "But it was something you remember a long time.

Douglas, who is the CEO of Weather Nation, a company that outsources video segments to local and national news clients, said the historic storm was remarkably intense and sudden.

"Meteorologists call it a 'bomb,' which means the air pressure fell at least 24 millibars in 24 hours," he said. "Those winds can reach 40, 50, 60 miles an hour. It's close to hurricane-force. Thankfully, they're rare. Something like that whips up maybe once every 20 to 30 years."

A total of 154 deaths were blamed on the storm, which cut a 1,000-mile-wide path through the Midwest. Sixty-six sailors died in Lake Michigan after three freighters and two smaller boats sank. Two people died when two trains collided in the blinding snow in Watkins, Minn. Records show that 27 inches of snow fell at Collegeville, Minn. Drifts closed many highways, and many motorists left their stranded autos and froze to death before they could reach safety. About 250 St. Paul streetcars were marooned on their tracks overnight. A woman in New Brighton scrambled 14 dozen eggs to feed travelers stranded at her house.

The rapid drop in temperature and the strong winds combined to form a fatal mix, Douglas said.

"You literally had a 40-degree temperature drop in six to eight hours, and that's almost unheard of," he said. "People headed out in light jackets because the temperatures were in the 50s and 60s in the morning, and then a few hours later, it was in the 20s or 30s with gale-force winds and blinding snow."

Roloff, a retired grain trader who worked at the Minneapolis Grain Exchange, said he and Ehlers were lucky to have survived. Many of their friends and relatives did not.

"We had a friend from school, Gerald Tarras ... they found him the next morning," Roloff said. "His brother froze, his dad froze and his uncle froze. He survived only because they hunted with a pair of big Labrador dogs, and they laid alongside of him."

'WE'RE GOING TO BE DEAD'

The lumber company in Winona where Roloff worked as a bookkeeper was closed on Armistice Day for the holiday; Ehlers worked in the pharmacy department of a drug store and didn't get off until mid-morning.

As soon as Ehlers got off work, he picked up Roloff in his 1934 Chevrolet and the two men drove to a spot near Reads Landing, just north of Wabasha, where they stored a small skiff.

"You know, up until that point," Roloff said, "it had been a warm fall, and we weren't shooting all that many ducks all fall -- and then, all of a sudden, we had this bountiful harvest, and it was just going great. They were flying low, too. You couldn't miss."

After getting their limit -- 10 ducks a day back then -- they quickly wanted to find a way home.

"The snow had started to drive, and then it began to get dark, and we knew that we had better get going because we still had this body of water to cross," Roloff said. "But it took us 35 to 40 minutes to get back to this slough, and by that time, it was really starting to blow."

Roloff said he will never forget what Ehlers told him: "He said, 'Norm, we've got to make it. There's no alternative, or we're going to be dead,' " he said. "We knew that if we didn't get out, we didn't have enough clothes to survive. Frankly, neither one of us smoked at that time, so we never even had matches with us."

The men decided to drag their skiff down to an area of the slough where there was a large timber stand. They'd have a better chance of crossing the water, they figured, if they were protected from the wind by trees.

"The waves were about 2 to 3 feet high," he said. "We started out, and we got probably about six to eight feet out, but the water would bring us back, so we left our ducks and left our decoys -- but we had some twine, so we tied our shotguns to the boat. We figured if the boat went over, we wouldn't lose our guns."

The men slipped their hip boots down to around their heels, Roloff said. In case the boat went under, they wanted their boots to be pulled off their feet rather than fill with water and turn into deadly anchors.

Each man took an oar, and they knelt in the shallow boat to paddle across the slough.

"We didn't have anything to bail out the water, and by the time we got to the other side, over half the boat was filled with water," Roloff said. "Then we had to walk about 1 1/2 miles to get to the car. The car started, but we were cold, very cold."

The men stopped at a bar on the outskirts of Winona on their way home.

"We had to get some alcohol to thaw us out," Roloff said.

The next day, a lumber company executive asked Roloff to help him search for three employees who had gone duck hunting and hadn't returned. Two of the employees were found alive; the third froze to death.

"I think I recognized then that we were pretty lucky to come home," Roloff said. "They used the Winona city garage as a mortuary. They would bring the frozen bodies there to thaw."

A 'FRANTIC' STORM

Lemm was traveling back to St. Paul with her family from St. Charles, Minn., after a long weekend at her maternal grandparents' house.

Lemm, who was 12 at the time, said neither she nor her parents and three siblings were dressed for blizzard conditions.

"I was wearing a skirt and a sweater," she said. "No girls wore pants back then."

The snow started falling in Eyota, she said. By the time the family drove onto the Spiral Bridge in Hastings, the sky was black and the winds were howling, she said.

"It had wooden railings," she said. "I kept my eyes closed as we went over."

Their 1937 Plymouth sedan broke down near Battle Creek Park -- "that was when the blizzard was just about as frantic as it could be," she said. Her father, Elmer Hegland, who had lost his left leg in the trenches of France during World War I, couldn't get out to push, she said.

"We didn't have a blanket, and my mother never brought water or food on all the trips we made down there," she said.

Lemm's father flagged down another driver, who gave Audrey and her mother, Elsie, and two younger siblings a ride to the house at 1078 McLean Ave.

"They could not turn onto our street, so we had to walk four houses up," Lemm said. "And then we had to crawl up 17 steps packed with snow. I can remember the blowing wind. Luckily, we had a railing, because the snow was so packed in."

When they finally got inside, it was stone cold.

We had cast-iron radiators, and the coal-fired furnace was out," she said. "We had to start a fire in the furnace, and it took a couple of hours before the radiators were even lukewarm," she said. "I can remember crying because it was so cold I didn't want to go to school the next day."

Meanwhile, her older brother Jerry, 13, had persuaded their father to let him walk to a nearby service station to get a tow truck. But when he got there, there was no truck available.

"Fortunately, they wouldn't let him leave," Lemm said. "My dad, by some miracle, he got the car started, and then he drove to the service station and picked my brother up, and then, a couple of hours later, he got home."

She learned a few days later that the father of one of her classmates wasn't so lucky -- he was one of the duck hunters who died in the blizzard.

The odds of a similar occurrence are "very low, but not zero," Douglas said. "The Halloween superstorm (of 1991) was a poignant reminder that even in spite of weather models and a better knowledge of meteorology compared to 1940, there are still times when we're going to get caught with our Dopplers down.

"This profession demands humility out of everybody who attempts to try it, so there will still be occasions where we are surprised," he said. "The Weather Service has certainly come a long way -- and with local media and private forecasters and literally scores of weather models, I think it would be much tougher to get caught like we did in 1940 -- but the probability is not zero."

Mary Divine can be reached at 651-228-5443.

.

God, help me be the man that my dog thinks that I am.